From Tehran to Taipei: How can teams and technology work better together?

If forming teams to achieve shared goals is an imperative in human society, why do university student teams often struggle to build collaboration and intercultural skills as expected?

A conference of the International Association for the Development of the Information Society hosted by Western Sydney University in December 2017 brought together international researchers to share new insights and potential solutions on learning and integral technologies. The papers summarised address a similar theme: Are students in certain cultures or communities resistant to take on team and knowledge sharing skills, or is there something about the approach in universities that currently makes student team success less than optimal?

The papers point to a need to understand how student team formation in university courses can be improved for better learning outcomes. While offering insights on new approaches in team formation and the types of challenges which students respond to, the authors also prompt some further questions – such as:

Is knowledge sharing, team formation and collaboration a skillset that can be taught in universities?

Do millennial students already have these skills, but have they somehow unlearned them?

Do institutions actually constrain our natural capabilities for collaboration and knowledge sharing[1]?

Reza Samim’s presentation entitled “The Impossibility of Teamwork in Iranian University Classes” certainly doesn’t sugar-coat the perceived challenge in higher education in his country. Faced with a bleak overview by faculty members of their students’ team-working abilities, Samim considered the Iranian university culture could account for a verdict of weak student approaches to teamwork when compared to the more “organic, public benefit oriented European institution”. However his review of a national student survey found some familiar underpinning challenges for students working in teams which included; team size (more than three is troublesome), students’ ability to share authority is poor and there was often a failure to engage inactive and passive team members. His conclusions on developing social trust and managing students’ preference for individual learning are reflections shared by those of us facilitating student team programs in other places.

A study by Chung-Kai Huang and colleagues in Taipei of 262 business undergraduates who participated in team based learning (TBL) through a flipped classroom[2] approach, looked at personal attributes which are considered important for effective team operation. Although the students surveyed identified potential value from learning and sharing knowledge with others, the researchers noted that the workload of TBL was generally unpopular and grade incentives were needed to motivate students to engage with the program. They also suggested a cultural expectation from their students for a more directed approach from their teachers could limit the benefits of independent learning, which is considered a key objective of TBL and flipped classrooms.

Understanding this challenge at an institutional level is an area of work being tackled by Peter Bryant from the LSE[3] who has developed a framework to focus on students and their interactions with institutional and personal technology. Bryant is looking to understand ways to better support collaborative learning as part of a larger institutional strategy by separating out myth and anecdote around blending technology with learning, such as; “social media distracts students from learning”.

Bryant’s charge here is that – “These myths create walled gardens of practice, where the calls for change are challenged by anecdotal assertions, rusted-on custom and practices, institutional inertia and sometimes outright resistance.”

Research as part of the LSE2020 plan logged 182 informal 3 minute video conversations and a survey of a further 250 students and found that students tend to describe ‘learning platforms’, such as Moodle, which are provided by the institution as the technologies which aid their learning. Although Bryant’s paper presents early findings, the work points to a richer parallel narrative about how students approach knowledge sharing outside main channels by forming ‘collectives’ through social media without the need for a teacher or some other “institutional gatekeeper”. There is also the finding that while students want more interactive approaches from their lecturers they are inclined to see institutional learning platforms more passively as a means to access the essentials to meet the course requirements. Bryant suggests this form of institutional approach to learning technologies potentially limits student engagement in how more diverse technologies can be recognised by both students and teachers as learning tools.

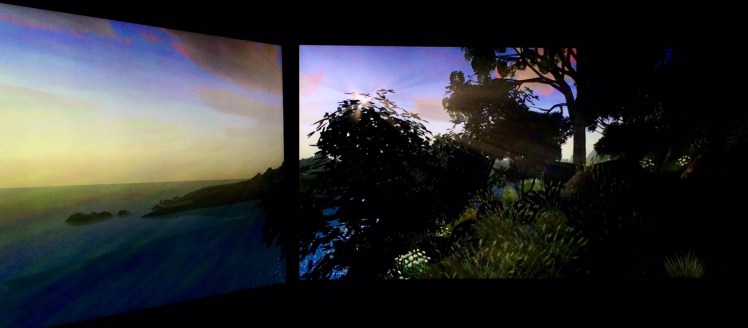

Thierry Karsenti and Julien Bugmann’s study of the educational potential of Minecraft in primary school children in Montreal suggests that we may start our learning journeys with a low barrier to knowledge sharing, team working and the ability to explore learning through technology. The researchers developed a 10 level program of tasks and small projects within Minecraft’s virtual environment for 118 students in 2 schools and provided a small reward (a coloured wristband) for each level achieved. Within a couple of weeks the researchers had to add a further 10 levels, making projects far more complex and ending with students learning to programme the game directly.

Working in pairs and small groups, the students demonstrated a high level of knowledge sharing and were soon working more as a collective across the class to assist other teams on a number of complex projects, such as building a virtual house to specification and recreating a replica Titanic. Compared to their peers at the schools who were outside the study, the Minecraft students showed educational benefits in 25 areas, including increased collaboration in project groups and mutual assistance between students.

In Chile the concept of enacting students to be producers as well as consumers of knowledge through online tools has been shown to be an important aspect of successfully building teams. Oriel Herrera and Patricia Mejias looked at students who worked in small teams to produce a range of learning products, from podcasts to collaborative maps and documents, for their fellow students to interact with. They found these peer-to-peer support activities over a range of subject areas (including engineering and biological sciences) showed potential to deliver highly positive outcomes for student learning through both knowledge production and as critical consumers of peer created materials.

Putting the ‘right’ teams together may also be one way of supporting better outcomes. With the growth of large student populations now learning online in MOOCs[4], enabling virtual teamwork has become the focus of work by Sankalp Prabhakar and Osmar Zaiane in Alberta, Canada. Working from a set of student attributes provided through MOOC registrations, Zaiane outlined the potential to harness particle swarm optimisation (PSO) to assign students to best fit teams. Whether applying this biological model gets us closer to meeting our compatible team mates is yet to be tested, but may potentially provide insights which could also support better team establishment for smaller, on campus courses.

Despite the geographic differences, the findings noted by a number of authors would not be unfamiliar to facilitators of student team programs in Australian universities. With our highly internationalised student cohorts, the Australian expectation of team learning as ‘sink or swim’ mode may not always translate easily into action or success for students. Here too there can be a tendency for some students to focus on grades or an eagerness to simply ‘get through’ team based programs. And yet there are student teams which gel early, work extremely well and achieve great outcomes, perhaps despite barriers being put in their way.

Whether the best long-term learning outcomes emerge from well-formed teams, intangible collectives or global swarms, there is no doubt more to learn from people experiencing university today and those who may participate in university programs ten years from now.

The papers referenced in this article were all presented at the International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) joint conferences hosted by Western Sydney University 11-13 December 2017.

Bryant, P. (2017) It doesn’t matter what you put in their hands: Understanding how students use technology to support, enhance and expand their learning in a complex world. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies 2017 Conference (pp. 67-74). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

Huang C-K., Lin C-Y., Lin Z-C., Wang C. and Lin C-J. (2017) Optimizing knowledge sharing, team effectiveness and individual learning within the flipped team-based classroom. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies 2017 Conference (pp. 191-192). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

Herrera, O. and Mejias, P. (2017) Peer instructions and use of technological tools: An innovative methodology for the development of meaningful learning. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies 2017 Conference (pp. 59-66). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

Karsenti, T. and Bugmann, J. (2017) Exploring the educational potential of Minecraft: The case of 118 elementary-school students. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies 2017 Conference (pp. 175-179). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

Prabhakar, S. and Zaiane, O.R. (2017) Learning group formation for massive open online courses (MOOCs). Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Educational Technologies 2017 Conference (pp. 129-136). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

Samim, R. (2017) The impossibility of teamwork in Iranian university classes: A study of one of the obstacles to the realization of sustainability in a country in transition. Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Sustainability, Technology and Education 2017 Conference (pp. 36-42). Lisbon: IADIS Press.

[1] Zach Wahl’s article on ‘Why People Fail to Knowledge Share’ in Image and Data Manager Dec-Jan 2018 gives an account of the challenges of knowledge management in a business environment. A mix of behavioural and organisational factors are recognised which can impact on effective knowledge sharing.

[2] The flipped classroom depends on students reading study materials to allow for activity based facilitation in face-to-face sessions rather than didactic teaching.

[3] London School of Economics and Political Science

[4] Massive Open Online Courses